Desert Storm Photos, Feb-Mar 1991

War can be viewed as the ultimate test of a person. Will you crumble? Will you cave in? Will demons and fears gnaw at you in the night? I went to the war seeking some of the answers to these questions and with the feeling that if I missed this war I might regret it for the rest of my life.

There is a certain amount of romanticism associated with war. Our culture and entertainment are full of references to it. I wanted to see where the truth was and the myth ended.

It was ironic to be in the snow in Kentucky when we were about to go to a Desert. From 82 degrees and rainy in Hawaii to 32 and snowing in Knox to 72, breezy and clear in Saudi Arabia. More about that later.

We got on a plane borrowed from Northwest Airlines for the war and headed off to Saudi Arabia via New York and Frankfurt. I spent 32 hours in that 747, something I hope never to repeat. We left Ft. Knox and headed to New York/JFK. I slept thru this portion.

When we got over the water and arrived in Germany there was snow everywhere. The inbound flight crew that was to take us to Saudi Arabia was delayed for 7 hours because of the snow. We tried to watch a movie, but the VCR was broken. So we sat. We couldn't leave the plane because they didn't want us to get "lost" so we had to stay in the cramped seats in full uniform with gas mask and rifle. The new flight crew finally arrived and we began the long flight across Europe and the Mediterranean to Saudi Arabia.

It turns out that one of the flight crew on the Frankfurt-Dhahran leg was from Kerrville, where my father lived, so I got to hang out with the crew for much of the flight. When we arrived in Dhahran they snapped my photo, and it ended up in the Kerville paper. Clock's ticking on that 15 minutes...

As we were flying over the Arabian penninsula, I looked out and could see smoke from gas flares on the horizon, and circles of irrigated crops growing incongruously in the middle fo the desert.

Naturally when we arrived it was the start of a new work day. I got off the plane feeling refreshed (not) and began the unloading process. Unload a couple hundred duffle bags (2 to a soldier, 350 soldiers) and rucksacks. This was something I got used to as the war went on. Being just an enlisted soldier, I was often detailed to do such grunt work, while the sergeants slacked off and smoked cigarrettes. On more than one occassion I suggested that they haul their own bags, and they just laughed at my impertinence. I would also ask for help from another enlisted soldier, and he would point to the rank on his collar, one rank above mine (almost nothing plus one still is not much) and decry that "I couldn't order him around" Get a grip. We all need to work together. I was to find this a problem as well. Selfishness is rampant in any human organization.

We stayed at the airfield for most of the day. We got a place to sit out in the open off the end of the tarmac, were served some food, and waited. Towards evening several NCOs came out and started calling off names, and we were broken up into 3 groups:

A Cavalry Regiment has around 7,000 troops compared to an Armored Division's 20,000, yet they have the same number of tanks. A cavalry regiment also has its own helicopter, air defense, Intelligence and artillery battalions as well. What Cavalry Regiments lack are infantry and many of the support troops. The shooter to clerk ratio is very favorable in the Cav. Almost no infantry and fewer support troops make for a faster and more efficient force to find the enemy and pin them down, until the heavy divisions can lumber up and squash the enemy like a bug.

We were equipped with 125 of the latest most bad-ass piece of armor in the world (as voted by all participants in the conflict) the < ahref = "http://www.army.mil/cmh-pg/books/www/255a.htm">M1-A1 HA Abrams Main Battle Tank. 72 tons of depleted uranium, steel, and aluminum. 1500 horsepower from a gas turbine. A 120 mm main gun that could shoot through BOTH sides of an Iraqi tank. 4 men made it go and the rest of us tried to keep up and keep them fueled. They use around 300 gallons of diesel fuel each per day.

The Bradley is hampered because it is too lightly armed or armored to be a tank but too tall and noisy to be a stealthy personnel carrier. It truly tried to be everything and ended up pleasing noone. We had monumental failures of the fuel filters (three of them, thw most commonly plugged one was of course the one hardest to get to) and transmissions in these machines. One was in such bad shape we simply blew it in place with explosives and thermite grenades rather than trying to recover it.

One day a Specialist poked his head in the tent where I was staying and said "Hembrook come out here" He introduced me to a pair of Captains. They worked as liason officers and they needed an enlisted guy to drive them back and forth to other units so we could share our maps and plans. Woo Hoo! I had a job.

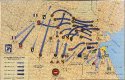

The 3rd ACR sat on the eastern edge of the XVIIIth Abn Corps. The unit immediately east of us was the 2nd ACR, which was stationed in Germany at the time. The 2nd ACR was the western most unit of the VIIth Corps. As a liason driver, I drove a Captain back and forth between the headquarters of the 3rd ACR and the 2nd ACR. This was about a 50 km drive through featureless desert. The general navigation technique was for us to drive about 5-10 km, stop, get out, and use a compass to get a landmark on the horizon. Then I would drive towards that landmark for another 5 km or so, and we'd check and find another landmark, and so on. Little bunny hops.

Driving across miles of featureless sand could be an adventure. Supply routes had been delineated across the desert by driving a road grader across the desert with the corner of the blade dropped in the ground to dig up a trench of sand along the route. One grader cut the left margin while a second several yards away cut the right margin. As long as you stayed between the two margins you were on the "Main Supply Route" or MSR. For a small vehicle like the Pajero, crossing over the MSR trenches was an adventure. Too slow, and you would hang. Too fast and you beat the vehicle up badly. As in many adventures in life, balance was the key.

We routinely drove the vehicles out there in 4WD mode, because the surface was loose enough to warrant it, and there was little worry about damaging the vehicle. This came in handy when you came to the occasional dust puddle. What's a dust puddle? Well, for millions of years the sand in this region has been kicked around back and forth by the winds. Eventually some of it gets ground down into dust finer than flour. This dust can accumulate into low lying areas. You don't know it until you hit one. Your front axel pops over a little ridge, adn suddenly you are awash in fine pink dust. Your best advice is to floor the accelerator pedal, straighten out the steering wheel adn hope that you have enough inertia to keep from bogging down. Windshield wipers do help a bit...

After a couple hours, we got to the 2nd ACR. We found their TOC (Tactical Operations Center, where the maps are drawn and plans made) and we would trade information, tracing their lines of battle onto our map and vice versa. After some discussions, we drove back. By this time it was getting dark, and we would drive by moonlight. Headlights were forbidden, so we would make do on our naked eye's night vision abilities. No NVGs (night vision goggles) or GPS sensors for us, just dead reckoning with the compass.

The last ten miles were navigated in pitch dark by our ears and noses. We could hear the hammering of diesel motors, generally generators, sometimes vehicles. We could also smell the tobacco smoke, diesel fuel and the smell of cooking food and garbage from quite a ways downwind. When we arrived at the edge of the base, we were stopped by a guard. The challenge/password was "Moisture" and "Packet". So the fellow asked me if I had any Moisture in my vehicle, and I replied that I had a whole packet. We were let through without incident. So many people were keyed up to get the first kill of the war, that fear of fratricide was a constant in the back of your mind. Driving a blue truck didn't help any.

That's when we went thru the breaches in the berm and began a nearly 400 mile drive from the border to the Ar Rumayla oil fields and Basra in less than a week.

So did I get one of these spiffy pieces of heavy armor described above for my personal chariot to carry me to victory? Nope. When G-Day rolled around we didn't feel like getting shot for terrorists so we ditched the Pajero. I bummed a ride in a HMMWV and rode over the border in style.

The Captain I had done liason duty with was assigned to the Mapping and Plans section of the headquarters, so I ended up following him.

I took over driving the section's 2.5 Ton truck. The classic Army "deuce and a half." The truck was older than I was (Built by Kaiser Jeep Corporation, which merged with Nash-Rambler to form American Motors in the '60s) but worked well. Selectable 4x6 or 6x6-wheel drive with a transfer case (2:1 step down), 5-speed manual shift, and a 6-cylinder turbodiesel engine (no muffler, just a straight pipe coming up out of the front fender near the passenger's ear. You had to wear ear plugs to drive it, conversation in the cab consisted of grunts and monosyllabic words). Top speed was 56 mph in 4x6 or 28 in 6x6.

We kitted the truck and its trailer up with plywood sheets to create an office on the bed of the truck so we were kept cool and non-sandy. It towed a trailer full of maps equipment and even a blue print machine! I was in the mapping and plans section so I guess all this would come in handy.

Along in the headquarters was a neat little section of 6 M577 armored offices, which would park together and set up canvas extensions to make an "office away from the office"

The details of the war are recounted more accurately in many other places, but the rudiments are:

The 3rd ACR was responsible for keeping the right (Easternmost) flank of the XVIII Corps safe. We spotted concentrations of troops and shot the hell out of them, or pinned them down until the heavys could get there. We were involved in some serious fighting, including some of the "Turkey shoot" along Highway 8.

The Headquarters Troop that I was in stayed very close to the front, no more than 10-20 miles behind the lead elements. This meant we were in range of artillery and missiles for most of the campaign. In fact we know of one artillery strike called in against us. It was the British! They saw a concentration of troops in the desert, and called in the coordinates. We immediately scrambled and tried to get the hell out of there before steel rained down from the sky. The artillery tubes were loaded, and the guns ready to fire when we got the fire mission called off by identifying ourselves to the British. That was close!

There was a reasonable amount of confusion during the combat. We had a M88 Armored

Recovery Vehicle (Tow truck for tanks) show up in our area.

As we were driving across the countryside looking for bad guys, we got to take in the natural surroundings.

More camel pics. These were raised by Bedouins. G+2

The low line off to the side of the photo is a Bedouin tent city. G+2

I was in charge of inventorying captured small arms. The captain I worked with

identified the captured vehicles. Here's some of our haul:

A 12.7mm DShK Heavy Machinegun. Standard Soviet heavy machine gun used on tanks and

other vehicles.

Fifty-Seven Millimeter Recoiless Rifle. Obsolete for the most part in the west, these

are shoulder or tripod ired guns that shoot gas out the back to counter the recoil

forces of the projectile fired from the muzzle.

Me in the hatch of an Iraqi BMP 1 Armored Personnel Carrier. I am wearing a Iraqi

tank Colonel's jacket and a russian fur lined tanker's helmet that was still neew

in the box. Items on loan from another soldier who helped clear the tunnels at Ar

Rumayla.G+5

We also blew up a lot of captured ammunition and bombs. These went off

fairly regularly. G+8

Click here to return to the Travel Page or here to return to my homepage.